Every so often, people come after Emily Wilson with pitchforks on social media for her translations of Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad. The latest flare-up dominated my “X” feed until I felt like writing the lengthy response you see here.

Wilson is a professor of classical studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Prominent X users have called her Odyssey “abominable, a crime against the classics,” and “a political manifesto advocating gynocracy” which “can in no serious way even properly be referred to as a translation.” The most concise offering was “wow this translation sucks.”

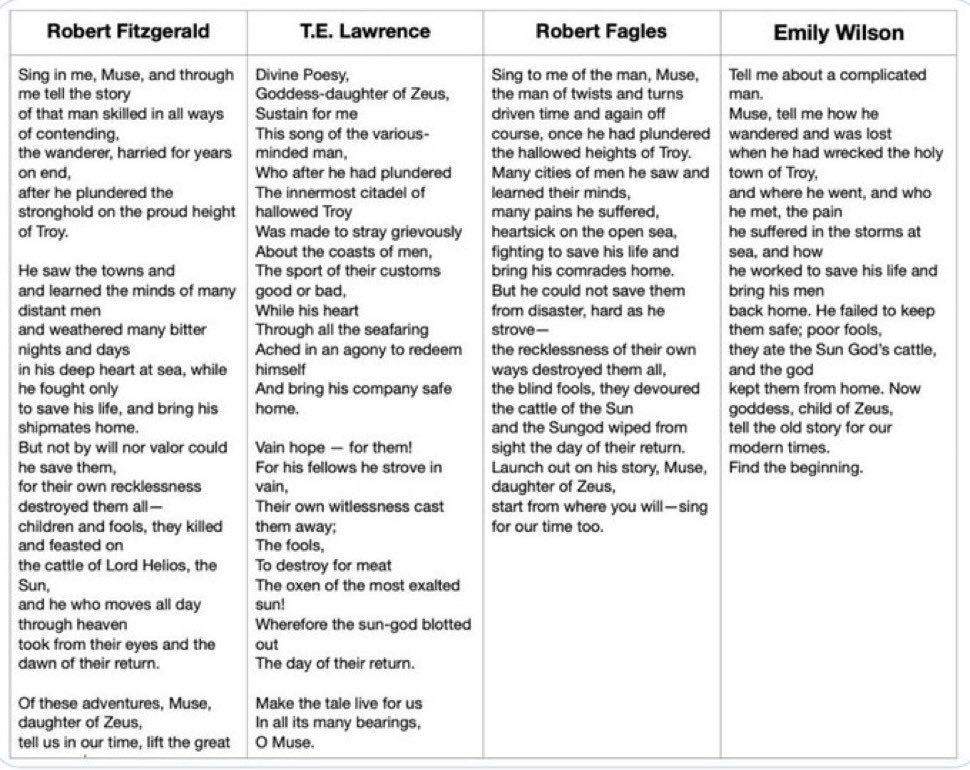

The translation does actually have a lot of fans. But why do some people hate it so much? In most cases, it’s a combination of the style (which as you can see in the image above is quite different from previous English versions) and her general perspective, which is typical of a current professor of literature at a prestigious university. “Making visible the cracks in the patriarchal fantasy” is one of her stated goals; her hobbies probably include problematizing things, like bodies and spaces, and sitting with them.

Had her interviews given off more of an “I just really love Homer” vibe, the pitchforks might be safely in storage. One also wonders how the world would have received this translation with a masculine nom de plume and no interviews. Alas, we can’t know. But according to one tweet, “our gripe with Wilson isn’t about the translation itself, it’s that she has so cynically capitalized on our current political/activist moment.”

When you put it that way it makes sense. However, many other commentators insist the translation itself is terrible, regardless of whether Wilson is cynically capitalizing on things. How can we judge this? Let’s consider some criteria.

1. Does it tell the same story as the original?

That’s a pretty low bar, but long ago — in the Middle Ages, say — you could write a new version of a story in your language and slap on the same title it had in the source language, even if the poetry was all yours and you added new incidents and characters. Wilson clears this bar easily. One might argue that her translation subtly encourages readers to interpret the story a certain way, but it’s the same sequence of events with the same cast of characters. She didn’t rewrite it from a siren’s perspective or anything weird like that.

2. Is it well-written in English?

Anyone can weigh in on this criterion. Unfortunately, those who do will never reach a consensus.

3. Does it give readers an accurate sense of the original?

This is what matters most to modern scholarly types. The academic standard is that the translation should reflect all the linguistic and narrative elements of the original as closely as possible while still being decent English. A friend of mine once bombed a Classics essay on Euripedes’ Bacchae because all her quotes came from a very free adaptation by Wole Soyinka — so free as to be considered a new work inspired by Euripedes, rather than a translation of Euripedes.

Wilson’s translation would pass the test that my unfortunate friend’s source failed. She is certainly aiming at modern standards of accuracy, as you can see from her Substack, where she gives detailed accounts of how she made her choices and how they compare to other versions.

In order to weigh in on this question of accuracy, you do have to have substantial expertise in Homeric Greek. I don’t, so I won’t. But I can say that in her writing I recognize the thought process of a serious translator making the kinds of decisions all translators make. So that one guy on X was definitely wrong to say it “can in no serious way even properly be referred to as a translation.”

Here is a negative review of Wilson’s Iliad by someone with the necessary expertise and here is a mostly positive one of her Odyssey. Both are interesting and demonstrate the level of knowledge required to evaluate it as a translation.

Although…there is something to be said for judging a translation entirely by criterion 2. “This is bad English writing” is a fair critique. I would just advise critics to make that clear, since “this is a bad translation” usually implies inaccuracy, and most of us can’t judge that. Sometimes translations are hated because they are hard to read, and that seems legit, with the caveat that the translator may simply be giving you an accurate sense of how hard it is to read the original. (Cyril Edwards’ Parzival springs to mind.)

Accurate translators are also supposed to “bring over” style and register. This raises several difficulties. For example, ancient poems are archaic from our perspective, but once they were fresh. Whenever we translate something from long ago, we have to choose where in time to locate our language.

When I translated an adventure story about Germans seeking their fortune in Papua New Guinea circa 1910, I tried to make the characters sound a bit like Richard Hannay; i.e. I tried to locate the English in their time. That’s the relatively recent past, so it wasn’t that hard to do.

But there was no English in Homer’s day, not even Old English, so English translations necessarily displace his work in time. What time do you pick, then? Should you give the language a Shakespearean feel? That would be consistent with how the poem seems to us and what kind of status it has in our canon. You could argue that even if Homer’s Greek has a rather stark and simple style (as Wilson claims it does), we should adorn it until it sounds like what we English speakers expect from great epic poetry. “Modern English is not a bardic language,” said one rando, voting to give it an archaic style. He has a point.

Someone on X compared Wilson’s work to the No Fear Shakespeare series. If you haven’t seen these, they are study aids that suck all the poetry out of Shakespeare’s plays until they lie, mere desiccated husks, on the floors of classrooms where students might as well be reading terms and conditions for downloading software. Quite a diss, in other words. This comparison presupposes that Wilson has “dumbed down” Homer but she claims precisely the opposite – that others have embellished Homer and hers is the more accurate version.

Wilson’s choice of iambic pentameter is reminiscent of Shakespeare, but her language itself sounds contemporary. I was amused to learn that Wilson’s Odysseus begins his slaughter of the suitors with “Playtime is over!” No good, said some commenters, it sounds like a Hollywood action movie. Well, said others, perhaps this was the equivalent in its day and this line hits you the same way the original line hit the Greeks. Then again, this review asserts that Homeric poetry had a distinctive poetic language that sounded at least vaguely archaic in its time, drawing from “vastly different centuries of Greek language and culture.” We might find an English equivalent of that in Howard Pyle.

At any rate, these are decisions that must be made and you can’t find a solution everyone will agree with. Religious people will never stop arguing over whether the Bible or the liturgy should be like bright, new copper or have the green patina of age, and we’ll never collectively decide whether Homer’s Odyssey should “sound ancient” when translated into a language that, again, did not exist when it was written.

If you’ve followed the colorful discourse about whether Wilson is murdering Homer and corrupting our youth, this is a good time to reflect on why there used to be so much anxiety about Bible translations. I’ve written something about that as well.

Leave a Reply