I grew up in a mainline Protestant church, where my family always spent the organist’s intro to a given hymn checking on who wrote the words, who composed the music, what country they were from, and when they lived. If we spotted someone who was famous outside of church, like Haydn or Arthur Sullivan, there was a chance for some gleeful pointing and whispering before we belted out the first few bars.

Do this often enough and you will find one name popping up with alarming frequency: Catherine Winkworth.

Germany is to hymnals what China is to Wal-Mart. Remove all the German tunes from an old-fashioned hymn book and you will be left with a sad little pamphlet. And in many cases, it was Catherine Winkworth who did the translation that allows us to sing them in English. Occasionally I have heard a really solid German hymn tune and wondered if I could be the one to provide an English text for it, but no – Catherine Winkworth had beaten me to the job, every time.

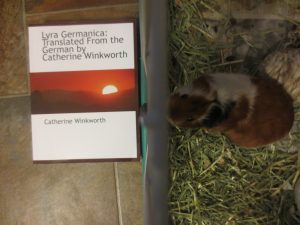

So I fell to wondering: who was this lady? I found her book of hymn translations, Lyra Germanica, on Amazon. My brother was kind enough to buy it for me for Christmas:

It contains the translations and a preface by her. To learn about her life, however, I had to look elsewhere. A few websites offered basic biographical information, but to know what kind of a person she really was, you need to go to Google Books and read the memoirs of her sister, Susanna. In summarizing them, I was going to say, “I read them so you don’t have to!” But in fact, this is an extremely interesting book, so if you enjoy my summary, go read the whole thing.

Born in London in 1837, Catherine was raised in a family of devout Evangelicals with a rural background reminiscent of a George Eliot novel, except that none them turned out to be an odious hypocrite. Her maternal grandfather was banished from home by his father at age 18 “for becoming a disciple of Whitefield, and refusing to join in any worldly amusements.” Catherine herself was a good, intelligent and pious child. At 8, she was noticed by a family friend sitting with a Bible on her lap and reading the Sermon on the Mount aloud to her younger siblings. “What, Kate,” asked the friend, “Reading the Bible to your brothers?” “Yes,” she replied, “But I try to choose the parts that are suited to their capacity.”

Her family valued education very highly and was well connected in religious and literary circles. Catherine and Susanna were passionate about learning everything they possibly could in theology, the sciences, and humanities. Their mother died rather suddenly after preparing too vigorously for a dinner party. They ran the household until their father took a second wife, a superfan of Lord Byron who apparently excelled at her hobby of making realistic dollhouse furniture.

This was their cue to leave home and have some adventures – Catherine went with an Aunt to Dresden, where she had lessons in German and music, as well as visiting art galleries, the theater, and the opera (both of the latter being dominated, at that time, by members of the Devrient family, whose acting troupe Susanna’s book describes as “the best actors of Germany, perhaps for tragedy the best of any country”). Upon her return to England Catherine was in a state of intellectual ferment: “Her early beliefs had been rudely shattered and she was at this epoch much inclined to replace them by the worship of Art and Culture. Goethe was her chief instructor and guide, and her philosophy was a chaos.” However, she eventually settled into an ordered Anglican existence in the mold of Charles Kingsley.

It was Susanna who first expressed an interest in translation, specifically a book on the life of Niebuhr. When she mentioned this to the German diplomat Baron von Bunsen, he jumped at the opportunity to mentor her, encouraging her not only to translate the book but to add original research of her own. To this end he carted her off to Bonn and made her do scary things like ask the world’s foremost Niebuhr expert questions in German at dinner in front of other distinguished Germans. On the plus side, she got to waltz with the Prince of Prussia.

Meanwhile, Catherine also tried her hand at German to English translation, including “some German hymns that Susie and I are fond of, and [I] don’t succeed very well, but I like doing it.” Soon she was translating a hymn a day and succeeding rather better. They were published as Lyra Germanica and sold out within two months. Fan mail poured in.

“Mein liebes Fräulein Winckworth,” wrote Baron Bunsen, to whom the work was dedicated, “Das Herz treibt mich Ihnen Deutsch zu reden, da Sie mir meine deutschen Lieblingslieder, die heiligen Gesänge meines Volkes so herrlich verstanden und wiedergegeben haben.” The prominent Unitarian James Martineau thanked her for introducing them “to the English reader with the least possible drawback from passing out of their own language.”

A typical letter from Catherine to Susanna from around the time she began translating:

“First of all, I must read Mill’s Political Economy some day; and then I want to learn Latin and Greek and Drawing, and perhaps I shall have to translate, and then there will be occupation enough; and so as I said, I am very well satisfied with my prospects; though, according to the doctrines M. and Mrs. P. are preaching to me at the moment, I ought to be very unhappy, because I’m not married, nor likely to be at present. They have been going on at me so about it, in a regular married woman style, which I hate.”

The Winkworth sisters never did marry, but they knew everybody: Charles Dickens (“has a very rapid decided way of talking, and is excessively full of fun and spirits”), Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini (“Well, altogether he is simply the most wonderful-looking man I ever saw in my life. He may be any height he likes, he is so thoroughly manly-looking, you do not think of it”), French socialist “little” Louis Blanc, Hungarian patriot Lajos Kossuth, Elizabeth Gaskell, John Ruskin, Robert and Elizabeth Browning, and Charlotte Brontë (“One feels that her life at least almost makes one like her books, though one does not want there to be any more Miss Brontës”), as well as everyone who was anyone in the English clergy, e.g. John Henry Newman’s younger brother Francis Newman (“a beautiful face and winning smile”) and F. D. Maurice (“I like him because he is so despotic”). They were highly active in the Sunday school movement, which in those days was much more significant than getting children to cut construction paper in a church basement.

Film buffs used to enjoy playing “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” History buffs should start playing “Six Degrees of Catherine Winkworth.” In fact, I would wager that in every Victorian miniseries you’ve ever seen, there is a woman in the background who looks like an extra but is actually playing Catherine Winkworth. She’s one of the most important Victorian ladies no one – apart from the hymnal nerds – has ever heard of.

Thanks for this, fascinating reading. I too remember the name of Catherine Winkworth, and its remarkable frequency in hymnals.

Ooooooooh this is juicy. Love the bit about the background “reminiscent of George Eliot” but with no one turning out to be an “odious hypocrite.” Will have to look out for Catherine Winkworth in my future reading of Victorian biographies, etc.