Richard Wagner mined most of his opera plots from medieval sources. Here’s an intro to Tannhäuser:

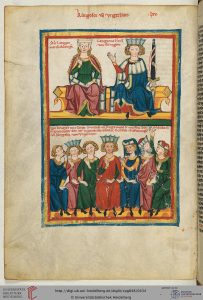

Legend has it that back in 1207 or so, Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia invited the most accomplished minstrels in the land to battle it out at the Wartburg castle in Eisenach. In German they call this the Sängerkrieg auf der Wartburg and the proper name for a medieval German minstrel is a Minnesänger. Here’s the original group photo, with Hermann and his wife Sophie above, and the Minnesänger below:

If you’re familiar with Wagner’s Tannhäuser, you know that the title character gets invited to this party and scandalizes everyone by expressing incorrect opinions about love. But Tannhäuser wasn’t actually invited — he belonged to a younger generation with a different party scene. In the original story, the offense was caused by Heinrich von Ofterdingen praising Leopold of Austria over Landgrave Hermann.

Now, if you were invited to show off your poetic talents at a castle, what would you say to your host, who took the time to organize this event and spent untold amounts on extra firewood, beer, small animals, and larger animals to stuff the small animals into? “Leopold of Austria really puts you to shame”? Of course not! You have better manners than Heinrich von Ofterdingen.

But manners aside, you’re probably not very interested in whether Hermann or Leopold was doing a better job of ruling a chunk of central Europe. So Wagner made a smart move here: he had the singers fight over love rather than politics.

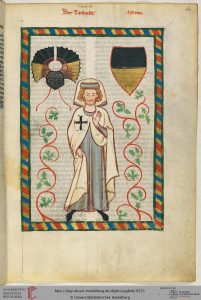

He did this by combining the Sängerkrieg legend with that of Tannhäuser. Tannhäuser was a real person; between 1245 and 1265, he wrote a number of bawdy lyric poems with a light, ironic perspective. A “penitential song” is also attributed to him, and the Manesse manuscript (a famous repository of medieval German poetry and source of the group photo above) shows him wearing the garb of the Teutonic Order:

These real-life elements laid the groundwork for the Tannhäuser legend: the poet finds his way into Venus’ mountain lair, where endless sensual delights await. Eventually, jaded by hedonism, he repents but the Pope denies him absolution. Tannhäuser despairs of forgiveness and returns to the infamous love den, there to await God’s final judgement on the Last Day.

In the late-medieval/early modern ballads, that’s it for him. In the opera, he is saved by the prayers of Elisabeth, a character inspired by Landgrave Hermann’s daughter-in-law St. Elizabeth of Hungary.

Wagner took a dualistic approach to this tale. In his version of the Wartburg poetry slam, the good poets advocate a purely spiritual love and Tannhäuser, the debauched poet, is the only one among them who does not regard sexual intercourse with prudish horror. This take has a few problems. For one thing, it creates a simplistic plot with little real human interest.

Wagner’s perspective was basically post-Christian, so he found it easy to imagine the medieval mind as committed to unbearably sharp distinctions with no grey areas, venial sins, or Purgatory. But a Christian society understands that only a tiny spiritual elite will throw themselves into thorny bushes to banish lustful thoughts, or refuse to participate in any conversation that does not revolve around The Divine Bridegroom. The rest muddle through ambiguously, hoping that the elite will do some of the heavy lifting for them.

Medieval sources reflect this ambiguity. The epic Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach has a moral structure under which real people could live; Wagner’s Parsifal does not. Tannhäuser suffers from the same difficulty.

As Sir Denis Forman, once deputy chairman of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, put it, “Wagner was not a believer and wrongly thought that the spirituality which had inspired Bach’s B Minor Mass, the painting of the Florentines and Dante’s Inferno could be used by any good pro as a mechanism to wheel out a holy plot. Which it can’t, because when false piety is rumbled there is nothing left but kitsch. That is why the pilgrims trudging to and from Rome are cardboard figures, why Elisabeth is no more than a nutcase, why the Minnesängers are a comical band of prefects at a pious public school and why Tannhäuser himself is a ludicrous figure.” (And Sir Denis was a Wagner fan.)

Another problem is Wagner’s portrayal of medieval love poetry. In the opera’s second act, the poets are asked to define the nature of love, whereupon they sing solemnly of unsullied fountains and cold stars whose purity they would defend with their last drop of blood. Even before Tannhäuser admits to having dwelt in the Venusberg, the other poets threaten him with swords just for mentioning “soft flesh” and “enjoyment in happy desire.” Angels and ministers of grace defend us!

Many people still have this idea of medieval courtly love — that you were supposed to honor your beloved so much you wouldn’t dream of touching her. But we really get this idea from Wagner and other dreamy Romantics like Hoffmann and Novalis. Although the Minnesänger discouraged casual hookups, the love they encouraged did also aim at physical consummation.

A handful of examples: Tristan and Isolde engage in flagrant acts of adultery, and author Gottfried von Strassburg treats it as an exemplary relationship with an aura of divinity. Wolfram von Eschenbach wrote dawn songs in which illicit lovers end up so tangled that “it would exhaust a painter’s talent to represent them”. Walther von der Vogelweide’s references to sex are often coy – “a little bird will keep our secret”; “let us break these flowers together” – but he’s also happy to inform us about the time he spied on a young lady stepping out of her bath. The humor in one of his poems hinges on a woman’s failure to understand what a love affair entails. In response to the man’s explanation that, “You should give a man your body in exchange for his. Lady, if you want mine, I’ll give it away for such a beautiful woman.” She responds, “I can’t think of anyone whose body I would want to take – that sounds like it would hurt him.” Mm.

They did like songs about worshiping unattainable ladies from afar, but they weren’t recommending it as an ideal — they were just seizing the chance to write mopey rhymes.

Minnesang was a morally dubious art form by strict Christian standards. Although individual churchmen sometimes acted as patrons for them, the Church generally disapproved of wandering entertainers. The music pretty much died at Landgrave Hermann’s court after his pious successors Ludwig IV and St. Elizabeth took over. They took a dim view of courtly love poetry with its potential to incite lust and its emphasis on ephemeral worldly things.

So the idea that Tannhäuser could scandalize a group of Minnesänger by praising carnal love is pretty silly. Far from being a guardian of moral purity, your average Minnesänger was probably hoping that when the time came he’d just scrape into Purgatory.

Tannhäuser has its good points. The hysterical chastity is tiresome and it’s a travesty of medieval culture; but of course what draws audiences to it is the music, not the medievalism, and on that point I really can’t complain.

Well, I knew nothing about Tannhauser except that it was an opera by Wagner. Thank you for educating me! By the way, did you know that the new Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada is named Richard Wagner? He’s Quebecois, of course.