For a time the Catholic Church was reluctant to approve Bible translations; now they are encouraged. What happened?

This post is for students, people caught up in arguments about history and religion, and anyone else who’s ever wondered about this issue. I hope it’s a useful introduction to the topic. If you find part of this post confusing, or if it doesn’t answer a question you would expect it to answer, leave a comment and I might make changes in response.

PART ONE: Practical Considerations

When people ask this question, they’re thinking about the mauve part of this map, where the head of the Church was the Bishop of Rome and the authorized version of the Bible was the Vulgate, a Latin translation of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew, written by St. Jerome in the late fourth century.

The first thing you need to understand to get a handle on the issue is how the linguistic landscape of Europe made Latin the favored language of education.

As Walter J. Ong explains in his excellent book Orality and Literacy, “Between about AD 550 and 700 the Latin spoken as a vernacular in various parts of Europe had evolved into various early forms of Italian, Spanish, Catalan, French, and the other Romance languages. By AD 700, speakers of these offshoots of Latin could no longer understand the old written Latin, intelligible perhaps to some of their great-grandparents. Their spoken language had moved too far away from its origins.

“But schooling, and with it most official discourse of Church or state, continued in Latin. There was really no alternative. Europe was a morass of hundreds of languages and dialects, most of them never written to this day. Tribes speaking countless Germanic and Slavic dialects, and even more exotic, non-Indo-European languages such as Magyar and Finnish and Turkish, were moving into western Europe. There was no way to translate the works, literary, scientific, philosophical, medical or theological, taught in school and universities, into the swarming oral vernaculars which often had different, mutually unintelligible forms among populations perhaps only fifty miles apart. Until one or another dialect for economic or other reasons became dominant enough to gain adherents even from other dialectical regions (as the East Midland dialect did in England or Hochdeutsch in Germany), the only practical policy was to teach Latin to the limited numbers of boys going to school.” (p. 112)

In other words, for much of the middle ages, if you wanted to translate the Bible into the vernacular, the first question was: Which vernacular? If you were in the German-speaking world, the answer couldn’t just be “German,” because there was no single standard form of German. Depending on where you lived, you might call the supreme being “God,” “Got,” or “Kot”. If you wanted to write “I believe in God the Father almighty,” your location would determine whether you wrote “Ih gilaubu in got fater almahtigan,” or “Gilouiu an god fader alomahtigan,” or “Ec gelobo in got alamehtigan fadaer”. Whatever you wrote, its geographical reach would be quite limited.

The vernacular also changes over time, whereas Latin—while not entirely immune to modification—is immensely more consistent as generations go by than the language people are shouting at each other in the streets.

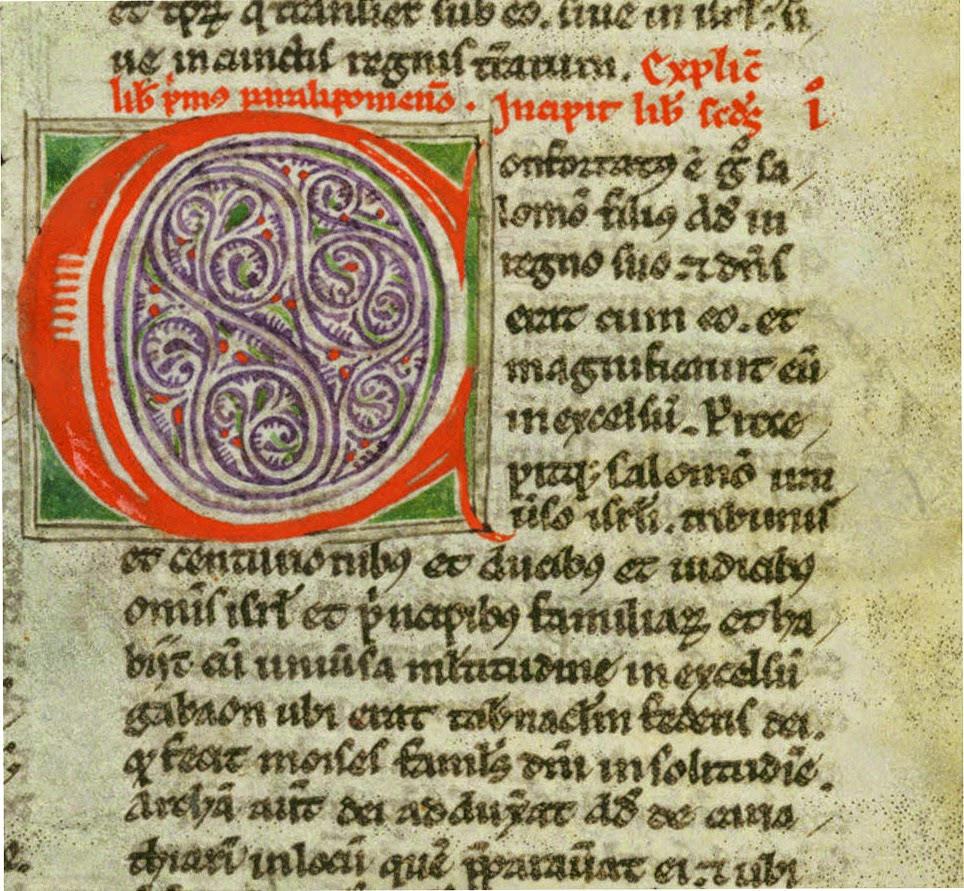

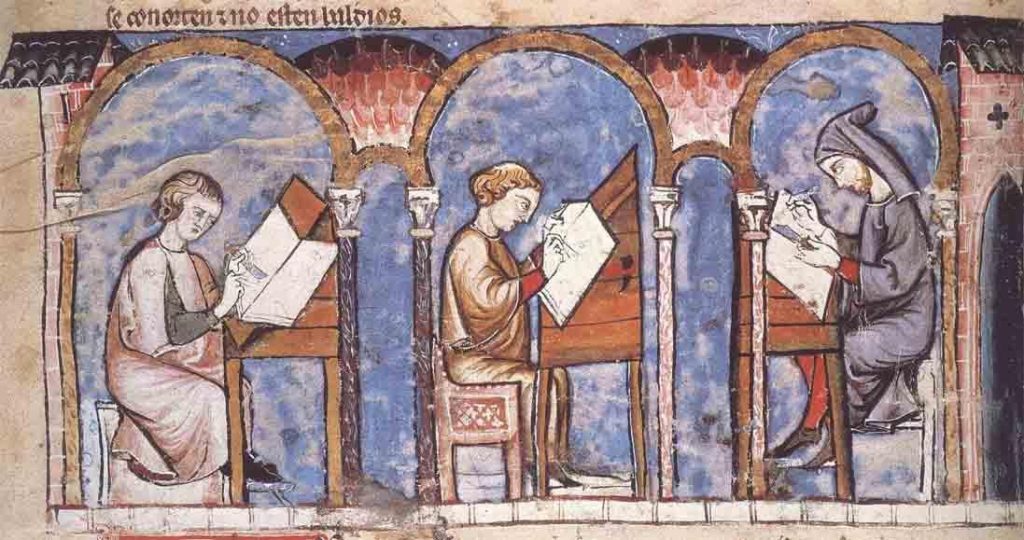

Bear in mind, as well, that books required an enormous amount of time and effort to produce. Someone had to sit in a chilly scriptorium scratching away at parchment or vellum (itself laboriously produced from animal skins) with a quill, which had limited mobility and needed to be dipped in liquid ink repeatedly. Here is a good video about how books were made in the middle ages. In short: it took a while.

And then the translation process itself takes time. Consider how long it takes to think through the best way to translate each line of the Bible. That’s still the case today, but it’s even harder when you’re translating into a language that doesn’t yet have a large body of prose writing that could inform your style and usage.

In the time it might take you to produce a single vernacular Bible of limited utility, you could teach Latin to a room full of young lads who could then use it to read not just the Bible, but other important books as well. What’s more, since schools all over Europe were teaching Latin, your local boys could go on to communicate easily with scholars in other countries. All that had to be done to make key works accessible to people in different times and places, and enable them to share their own works widely, was to teach them Latin. For a long time, this was the most efficient system available.

It worked so well for so long that when vernaculars began to coalesce into standardized forms and other systems became possible, people were not necessarily in a hurry to change it.

PART TWO: The Problem of Translation

There is no perfect translation and every translation is also an interpretation. This is unavoidable.

A legend is told about the Septuagint, which is an ancient translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. The story goes that 72 translators gathered in Alexandria. Each of them worked in isolation on his own version of the text and when they had finished and compared their work, behold, it was found that everyone had written the same words.

That would indeed be a miracle.

The translation of authoritative religious texts is always a cause for concern. The legend of the Septuagint soothed the anxiety of those who relied on it. Vulgate readers could take comfort from Jerome’s status as a saint—one could assume the Holy Spirit was guiding his pen. But the guardians of orthodoxy were not eager to see his translation turned into hundreds of new, experimental translations.

The problem of translation is a problem for everyone, not just medieval Europeans. For example, the customary way to deal with this problem in Islam is for only the Arabic text of the Koran to be truly considered “The Koran”; early translations had titles like The Meaning of the Glorious Koran or An Interpretation of the Koran. I have a copy entitled The Holy Qur’an with English Translation. It contains the Arabic text, and only that part is actually the Holy Qur’an.

Having just checked Amazon, I’m not sure how strict publishers are anymore about the titles they put on translations of the Koran. But I did find interesting comments (on three different versions) that reflect common concerns about the translation of holy books:

- It’s a non-sectarian translation. It’s neither Sunni nor Shia. It just translates the Quran. No interpretations and explanations. [mmm-hmmm – Ed.]

- I give it four stars only because it was clear to me in reading it that the anonymous translator ensured that sometimes difficult and controversial passages received the kindest, most Islam-supportive interpretations.

- I suspect Arberry’s translation of the Holy Koran is not without flaws….again, this is a translation, not the Koran itself as God’s word. For this reason, I assigned 4 stars to the translation, but a perfect score to the Holy Word of God as written in the Koran.

To return to the Bible, it’s important to understand that Catholic theologians of the Vulgate era were leaning hard on the Latin text to support Church teaching. What if the text became unmoored by translation into multiple languages, passing through the interpretive faculties of many people, some of them, perhaps, devious heretics? What might come out on the other end and what problems might it cause? There were concerns.

But here I should say a bit about the translations that were in fact made in the centuries before the Reformation, despite all the above-mentioned reasons not to bother translating the Bible.

PART THREE: Pre-Reformation Bible Translations

You may have finished part one and thought, “That’s fine for the few boys who went to school, but what about everyone else? How did they find out what was in the Bible?”

That’s a big topic, but concisely: sermons, other preaching, storytelling, images, mystery plays, popular devotions, and sometimes, early translations.

As explained in part one, vernacular translations of the entire Bible were doomed to fail a cost/benefit analysis. But there were various translations of important parts of the Bible into local languages.

The Wessex Gospels are a well-known example of a translation into Old English, done in the late tenth century (ca 990).

Here is a sampling of German translations:

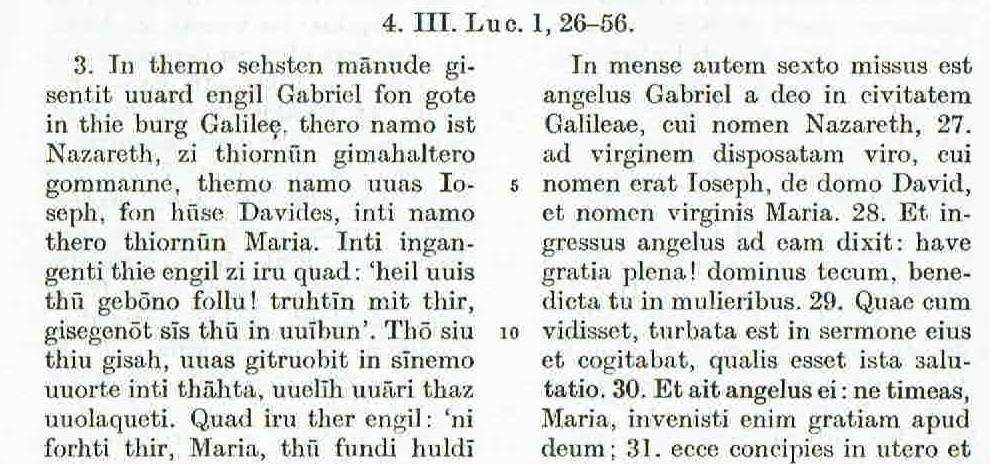

a ninth-century translation of a Latin translation of the Diatessaron of Tatian into east Franconian, seen here in a modern edition:

a psalm translation, also from the ninth century, into Alemannic. I put this one next to a modern English translation:

| Ps. 114 (116) Ih minnota, pidiu kehorta truhtin stimma des kebetes mines. Danta kineicta ora sinaz mir, inti in tagon minen kinemmu dih. Umbiseliton mih seher des todes, zaala dera hella funtun mih. Arabeit inti seher fand, inti namon truhtines kinamta. Uuolago truhtin, erlosi sela mina. kenadiger truhtin inti recter, inti got unser kenadit. Kehaltanti luzcila truhtin: kediomuoter pim inti arlosta mih. Uuerbi, sela mina, in resti dina, danta truhtin uuolateta dir. Danta erlosta sela mina fona tode, ougon miniu fona zaharim, fuozzi mine fona slippe. | I love the Lord, for he heard my voice; he heard my cry for mercy. Because he turned his ear to me, I will call on him as long as I live. The cords of death entangled me, the anguish of the grave came over me; I was overcome by distress and sorrow. Then I called on the name of the Lord: “Lord, save me!” The Lord is gracious and righteous; our God is full of compassion. The Lord protects the unwary; when I was brought low, he saved me. Return to your rest, my soul, for the Lord has been good to you. For you, Lord, have delivered me from death, my eyes from tears, my feet from stumbling. |

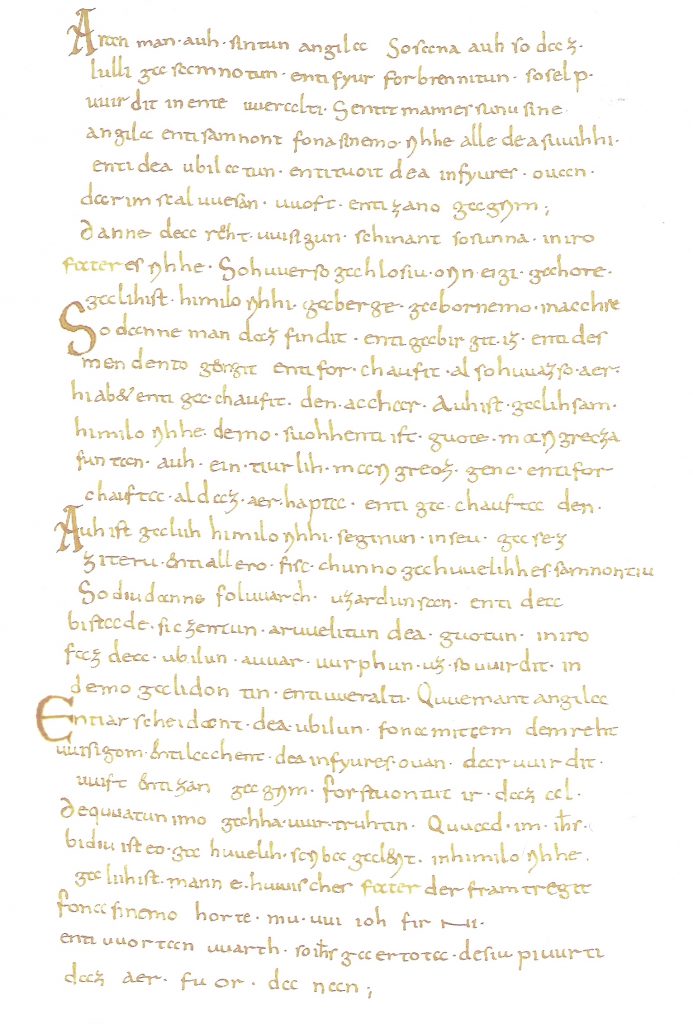

a translation of the Gospel of Matthew into old Bavarian in the early ninth century, now included in the “Mondseer Fragmente.” It is the earliest translation of part of the Bible into a dialect of Old High German. Here’s a photo of the original manuscript:

There were also loose translations, such as poetic retellings of Bible stories. The best-known is Otfrid’s Evangelienbuch, written, once again, in the ninth century. You can read the whole thing, and even click on each word for more info, here. It’s a charming work with poetic details. Of the angel Gabriel, Oftrid says, “Tho quam boto fona gote, engil ir himile. / braht er therera uuorolti diuri arunti. / Fluog er sunnun pad, sterrono straza, / uuega uuolkono zi deru itis frono.” (There came a messenger from God, an angel from heaven. / He brought the world good news. / He flew the sun’s path, the street of stars, / the way of clouds, to the holy woman.)

Interlinear glosses were another way of translating the Bible. A “gloss” can mean commentary in the margins of a text, but in this case it means a simple, word-for-word translation written in between the lines. These were especially for people who could read but didn’t have excellent Latin skills, such as nuns, well-to-do laypeople, and poorly educated priests. They helped people understand the text of the Bible, but did not constitute good translations on their own, rather like the song translations I discussed in my post “When bad translations are good.”

PART FOUR: The Crackdown

Bible translations were never completely forbidden, but by the late Middle Ages, they had become fraught and risky projects. As the tumultuous world of the ninth and tenth centuries gave way to a more settled world where no one had pagan grandparents, the Vikings weren’t coming and the Saracens were pretty quiet, and the Latin education system was exploding into a giant systematic-theology debate-fest, the spirit of evangelization gave way to the spirit of bickering about what the Bible really means.

The Mediterranean world in late antiquity had seen a long dance of heresies and councils, but western Europe was relatively placid in terms of heresy in the early Middle Ages. Until King Robert the Pious of France ordered the burning of alleged heretics in Orleans in 1022, no one had been put to death for heresy in the western Church since 383.

The controversies of the High-to-Late Middle Ages awakened the concerns mentioned at the end of Part Two: Who is doing these translations? Are they heretics? ARE THEY???

Medieval heresy and its impact on scripture is such a vast topic that I can’t provide anything like a comprehensive account. Instead, I’ll provide a snapshot of how these issues played out in one case. Here’s what happened when the Bishop of Metz got in touch with Pope Innocent III about a group of Waldensians in his diocese, as recounted in Medieval Heresy by Malcolm Lambert:

“Their [the Waldensians’] knowledge of the Bible was often remarkable. Children began to learn the gospels and the epistles. It was not unknown for an illiterate supporter to know forty Sunday gospels by heart, and in Austria in the thirteenth century a relatively objective Catholic observer recorded the case of a member who knew all the book of Job by heart.

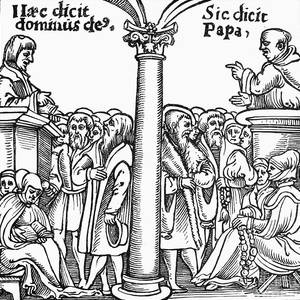

“Attitudes of churchmen towards vernacular translations (in so far as they were to be used by the common people) tended to be hostile partly because of the use made of them in practice by heretical preachers. When the bishop of Metz wrote to Innocent III in 1199 denouncing laymen and women who had commissioned vernacular translations of Scripture and relied on them for debating about their contents in secret gatherings and for preaching, the pope was slow to authorize repression.

“His chief concern lay with the unauthorized preaching. He asked the bishop to find out about the author of the translation, his intention and the quality of faith of those who used it—and about their attitude to the papacy and the Church. His reply to the bishop’s renewed complaint that some of them had been disobedient to Innocent’s requirements, alleging that they owed obedience only to God, was to commission three Cistercian abbots to go to Metz to investigate further and correct the laity where necessary. It is not known what happened, though a later Cistercian chronicle speaks of abbots burning translations in Metz. It was a likely outcome.

“Clearly Innocent was suspicious of an over-hasty bishop and anxious not to extinguish enthusiasm. He said that the ‘desire for understanding the Holy Scriptures and a zeal for preaching what is in the Scriptures is something not to be reprimanded but rather to be encouraged’, and it is significant that at the end of his pontificate, when he drew up constitutions for the fourth Lateran Council of 1215, he did not include in them any blanket prohibition of translations of Scripture. Nevertheless he also explained that ‘the secret mysteries of the faith ought not…to be explained to all men in all places…For such is the depth of divine Scripture, that not only the simple and illiterate but even the prudent and learned are not fully sufficient to try to understand it.’ Here lay the nub of the matter. The study of Scripture demanded training and skill; the use of it formed a part of the Church’s teaching and could not be divorced from it. If the use of translations came to be associated with teaching hostile to, or contemptuous of the priesthood, as was the case in Metz, then the translations were likely to be casualties. Repression of translations as well as of heretical preachers was the simple disciplinary solution, especially when local prelates had narrow horizons.” [- Lambert, Medieval Heresy, third edition, pp. 81-82]

Here Lambert gives us a good sense of the many factors involved in the Catholic hierarchy’s growing hostility to vernacular Bibles during the period. However, they couldn’t keep that cat in the bag forever.

PART FIVE: The Cat gets out of the Bag

By the early 1500s, the state of vernacular languages in western Europe and the advances in printing technology made Bible translations for popular consumption inevitable. It was around 1500 that a supraregional German “Schriftsprache” (written language) emerged, and it lay there waiting for someone to pick it up, put it in the Bible, and put that Bible on the presses. That someone was, of course, Martin Luther, who escaped the stake thanks to powerful friends who protected and promoted his translation of the Bible into German (New Testament 1522, entire Bible 1534). Luther’s open letter on translation deserves its own post. Perhaps I’ll do that next.

For now, I’ll briefly cover a few more factors that contributed to the liberalization of Bible translation, because goodness, this post is getting long.

Renaissance Humanists and their emphasis on original sources (“Ad fontes!”) drove progress in Biblical research. Important projects of the Reformation era included Erasmus’ Latin-and-Greek edition of the New Testament (first edition in 1516), and the Complutensian Polyglot Bible, a massive undertaking by scholars in Spain that began in 1502 and was completed around the time Luther wrote his 95 theses. This video is an ad for a facsimile of it; it’s worth watching for a thorough tour of its contents.

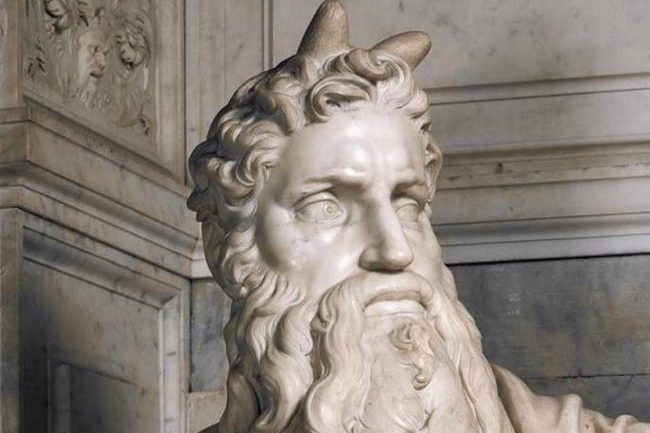

One result of that new scholarship was that it became harder to convince everyone to just chill and be content with the Vulgate—in part because people were gaining new insights from studying Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic, but also because their studies revealed errors in the Vulgate. For example, when Moses came back from talking with God, he had to wear a veil because his face was so luminous. But for some reason St. Jerome translated that passage as saying that Moses had horns. I mean I get it, Jerome, I’ve made mistakes too, but at least I didn’t make Michelangelo do this:

Between the exciting state of scholarship, German princes feeling fed up with Rome, and the magic of the printing press, it became impossible for the hierarchy to control and limit Bible translation and use as they had been wont to do.

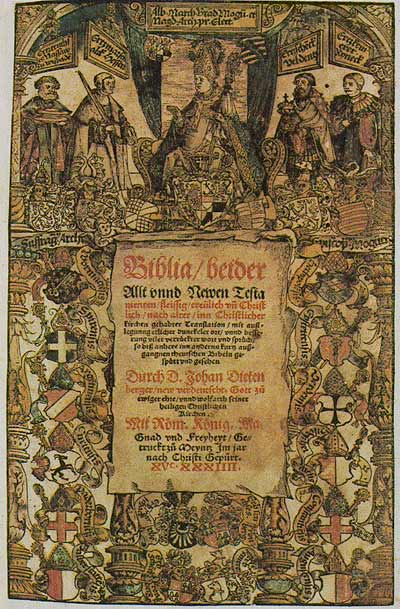

The only option left was for Catholics to get in on the act and make their own vernacular translations for popular use. In Germany, Dominican friar Johann Dietenberger published a German Bible (Biblia beider Allt und Newen Testamenten, new verdeutscht) in 1534.

And to cut a long story short, that’s how you eventually get to the array of Bible translations, Protestant, Catholic, “Amplified,” Non-denominational, scholarly, popular, groovy or otherwise that you can now purchase wherever books are sold.