People tend to think of machine-translation post editing as “easier” than old-fashioned translation.

But I’ve come to think of MTPE not as easier than traditional translation, but as requiring a different set of skills. Namely, the same skills required by find-the-difference puzzles.

Find-the-difference puzzles vary in difficulty, of course, just as MT jobs do. You might — especially if you’re working with an extremely cheap online translation service — get an MT job consisting of single sentence with one glaring error, in which case it feels like this puzzle:

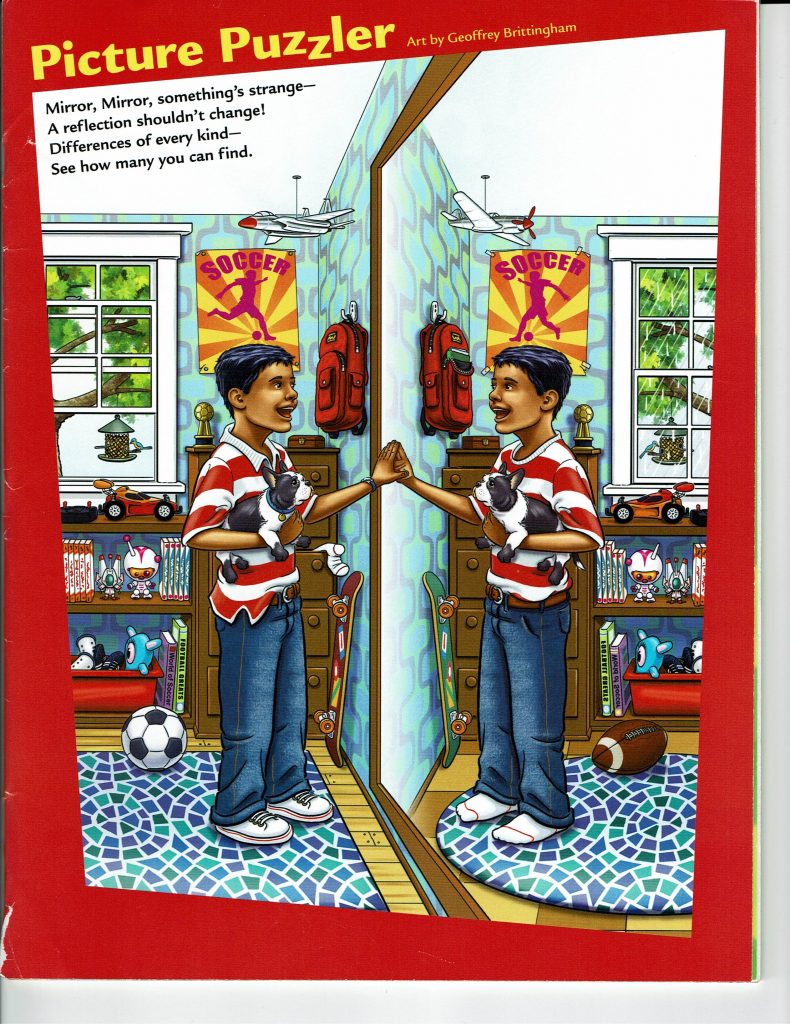

Or you might get a longer, more complex text with subtler errors, like this puzzle:

The worst scenario is a long text where the MT has done a mostly acceptable job. You compare 10 sentences in a row and they’re all fine. This makes you lazy and then you overlook the errors that do crop up from time to time. It’s like getting two versions of a crowded Brueghel painting and the only difference between them is that one person is missing a shoe.

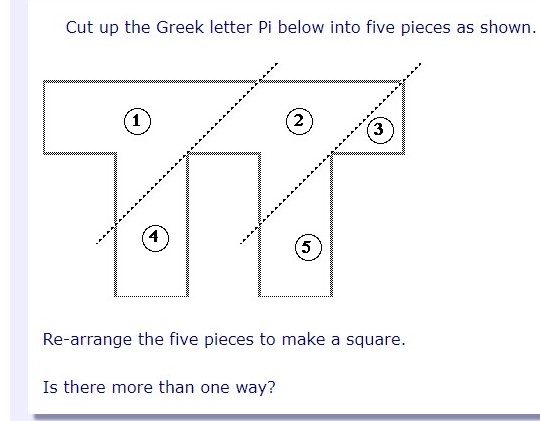

In any case, the mental processes required for MTPE are different from those required by traditional translation. I was going to say that translating the old-fashioned way is like unraveling a knitted garment and knitting it back up again according to a different pattern. But since my first metaphor was a find-the-difference puzzle, I should compare it to a puzzle. Maybe it’s like this puzzle:

Both jobs have the same goal, which is to produce a text that is correct and comprehensible in another language. They also require similar basic skills — in both cases you need to have a good understanding of two languages and decent writing skills in the target language (although it’s worth noting that MTPE doesn’t require excellent writing skills, just “premium mediocre” ones) but your brain is doing a different kind of job in each case. So I wouldn’t be surprised if some translators are better at one than the other. Perhaps the future of the industry will see a sharp division between find-the-difference people and rearrange-the-shapes people, handling different kinds of texts.

[“Picture puzzler” comes from Highlights magazine and the Pi puzzle from mathisfun.com]