Vienna has once again been ranked the world’s best city to live in. Apparently it’s won the Mercer Quality of Living Survey 10 years in a row and from what I saw on my last visit there, I’d say the honor is well-deserved.

But Vienna hasn’t always been such a great place to live. In the good old days it was probably the best place to develop your mad composition skills, eat delicious pastries, and get syphilis, but the actual living part was a challenge.

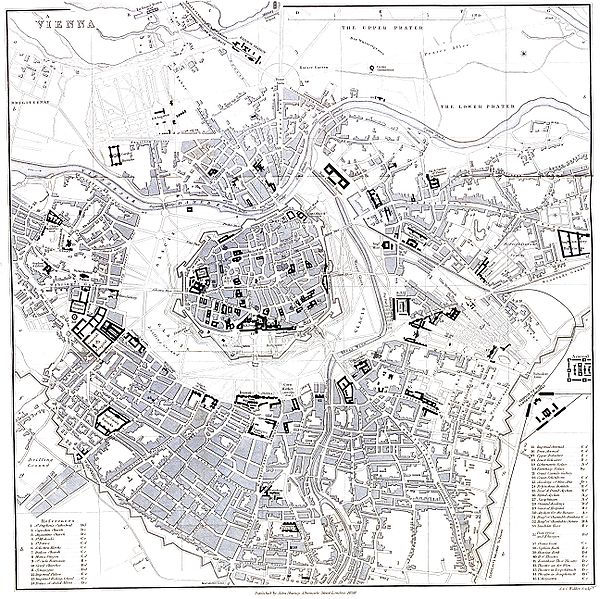

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Vienna suffered from an increasingly severe housing shortage. The city’s population increased roughly tenfold over the course of the nineteenth century. Although that wasn’t an unusual rate of urban growth for the time —and the fastest-growing capital in Europe, Budapest, had people living in trees — Vienna’s housing situation was still comparatively difficult. For one thing, at a time when most cities had already spread beyond their old walls, expansion of Vienna proper was still inhibited by its old fortifications and the military exercise grounds right outside them.

The city walls were torn down in the late 1850s and replaced by the Ringstrasse. This made room for expansion and new construction, driven mainly by tax cuts and private initiative. But it didn’t create sufficient, affordable housing for the city’s growing population. In fact, a speculative real-estate bubble where the security often rested merely on planned construction was a factor in the Vienna stock market crash of 1873.

So what were your housing options in Olde Vienna?

1. The street: If lying in the gutter wasn’t your thing, you could live under a bridge or in a little cave dug into a railway embankment. Young women sometimes turned to prostitution just to get a bed for the night.

2. Single-family house: In my town of 10,000 in the US, almost everyone lives in one of those. By 1910, there were 2,031,420 people in Vienna and only 5734 single-family homes. By my calculations, that’s one house for every 354 people, so you won’t be surprised to learn they accommodated only 1.2% of the city’s population. Scroll down this blog to see some lovely houses belonging to that 1.2%.

3. Nice apartments: You’ll see a lot of these if, like me, you mainly go to Vienna to commune with dead composers. For example, go here to see the building Franz Schubert was born in. His family lived in one room with a little kitchen alcove, but it was a pretty big room with windows and a courtyard where children could play, so basically a win. And in 1801 they moved to a nicer place. I assume by 1860 or so, anyone who occupied such a dwelling would keep a vice-like grip on it and sub-let only to the classiest tenants.

4. Bassenawohnung or ZKK – two names for the same kind of squalid apartment for the average citizen. The “Bassena” was a sink in the hallway, the sole source of running water for a number of apartments. It was also the place to exchange gossip. “ZKK” stands for “Zimmer, Küche, Kabinett” (“room, kitchen, closet”). These were generally 22 to 28 m², with a communal toilet out in the hall by the Bassena. Some tenement apartments had only 2 rooms (no closet) or really just one and a bit.

Not only were large families often crammed into these apartments, but because many of them needed help with the rent they also sub-let sections of the place to people who couldn’t afford, or perhaps couldn’t even find, an apartment of their own. Even in the smallest, most crowded apartment there was room for a “Bettgeher” (a “bed-goer” or bed lodger), who paid for a place to sleep and nothing else. He might get space in a drawer for his possessions if he was lucky. In the 1870s, Bettgeher and other sub-renters made up a quarter of the Viennese population.

“It is almost impossible to penetrate the secret of a Viennese apartment,” Ingeborg Bachmann wrote, “Even a person’s best friends cannot do it.” It’s not hard to understand why.

The popularity of the Viennese coffee house, with its cozy opulence, owes much to the fact that people were keen to minimize the amount of time they spent at home. The writer Peter Altenberg exemplified this strategy. He rented a hotel room to sleep in, but the Café Central was where he ate, worked, socialized, and got his mail – essentially, it was where he lived.

Scarcity of resources during the First World War made the housing crisis acute. The Imperial edict for the protection of renters issued in 1917 froze rent, which eased financial pressure on tenants but also turned the overcrowding problem into a homelessness problem when these same tenants kicked out their no-longer-needed Bettgeher. This sparked the Siedlerbewegung or “settler’s movement,” in which thousands of people moved out to the edge of the city to occupy land, plant gardens and build simple shelters out of wood they cut from nearby forests. Within seven years, the movement had grown into 30,000 families managing 6.5 million square meters.

The spirit of this movement flowed into the policy of the Social Democrats, who finally turned Vienna’s housing situation around in the 1920s with a building program for the working classes; their best-known accomplishment is probably the Karl-Marx-Hof. For more about Viennese social housing, with plenty of photos, see this or this or this or this. Interestingly, if you google “Paris housing crisis,” you get articles about how hard it is to find affordable housing in Paris today. If you google “Vienna housing crisis,” the top articles are all about how wonderfully Vienna solved its housing crisis.

If you live in Vienna nowadays, you can’t argue with Karl Kraus over a Mélange but at least you’ll have indoor plumbing and there won’t be a day laborer sleeping on your kitchen floor. As far as the average citizen is concerned, this is probably the best time in history to live there. It sure seems that way from this video by Thomas Pöcksteiner and Peter Jablonowski. Vienna is not forgetting to be awesome.

A Taste of Vienna from FilmSpektakel on Vimeo.

I got most of the info for this post from The Viennese by Paul Hofmann, Wittgenstein’s Vienna by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin, and articles by Michael Klein of TU Wien.

Leave a Reply